WWII Korean War Group of Historical Signifcance Frank Schwable USMC

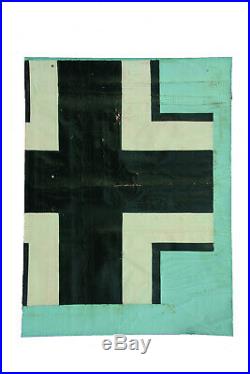

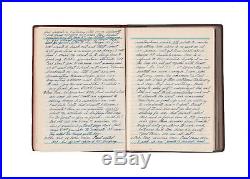

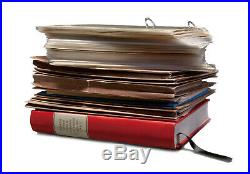

WW2/Korean War group of historical significance. There are 25 professional photographs taken of this group. The collection: His medals with all relevant citations, uniform & hat (named), eight aviators flight logs (including the Solomon Island campaign marking his night fighter kills), many photos, documents, typed onion skin report from North Africa and England, an iron cross cut out of a German glider in North Africa (with copies of drawings of the glider that he made for the Corps along with photos), two handwritten notebooks from his 1941-2 tour in England with sketches related to then top-secret Mark IV radar, telegrams related to his capture in Korea, his typed onion skin report about his internment and torture as a POW, a small diary kept during the Court of Inquiry (1954), an audio copy of the USMC oral history interview, a large bound version of his oral history published by the History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.

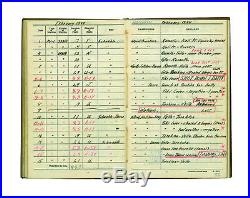

Marine Corps, Washington, and more. In addition to the Legion of Merit with Combat "V" and two gold Stars in lieu of second and third awards, Schwable was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross with three Gold Stars, the Air Medal with two silver stars in lieu of ten awards, the Nicaraguan Cross of Valor, the Second Nicaraguan Campaign Medal, the American Defense Service Medal with Base Clasp, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with four bronze stars, the American Campaign Medal, the World war II Victory Medal, the national Defense Service Medal, the Korean Service Medal, and the United Nations Service Medal. #1 begins in 1930 he was a 2nd Lt. #2 1932 - June 1933. #3 June 1933 - January 1935.#4 February 1935 - Sept. #5 October 1936 - July 1938. #6 August 1936 - September 1940. #7 October 1940 - April 1946.

#8 - Note: His last log is not numbered. It begins November 1953 and ends in June 1959. Schwable remarks in his oral history interview conducted by the USMC, that he never piloted an aircraft again after his last 1959 entry. I figured 28 years I had been able to get away with this, so that's enough.

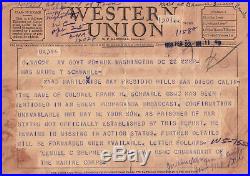

As I told you [the interviewer] before, one of them let me down. A Brief History: A richly documented group with plenty of history. In November 1941 Schwable was sent to North Africa as a Marine Corps observer. From there he traveled to England where he attended the Fighter Director school at RAF Stanmore Park, served as an observer with the Royal Air Force night fighter squadron at RAF Coltishall, and was briefed on England's top secret Mark 4 radar.In 1943 his squadron, VMF(N)-531, served in the Solomon Islands where he registered four night fighter kills. During the Korean War he served as Chief of Staff, First Marine Aircraft Wing, arriving there in April, 1952. Within weeks of his arrival he received word of a new assignment; relieve Colonel Gaylor by mid-summer as Commanding Officer of MAG 14. On July 8 he boarded a twin-engine aircraft for the purpose of observing the area over which he would soon command. Colonel Schwable's plane was shot down, he was taken prisoner (becoming the second highest ranking POW of the conflict), tortured by the Chinese over a period of nine months, and forced to make a false germ warfare confession.

After his release in 1953, Col. Schwable was put before a Court of Inquiry for his "confession". His case was a media sensation and stories about his capture, torture, and subsequent trial appeared in newspapers world wide NY Times, Time, Life, etc. The court determined that Schwable had resisted torture to the limit of his ability.

The most important outcome of his case was the creation of the U. Armed Forces Code of Conduct.

This is a very large collection and fills an officer's size footlocker. It is being released from my collection to fund an expedition to New Guinea to recover wreckage from a lost B-17, to be exhibited in our local museum. Books Published About Frank Schwable. Raymond Lech, Tortured Into Fake Confession: The Dishonoring of Korean War Prisoner Col.Forrest Pollard, Militaria From the Pacific War, Discovering Their Stories , P. 64-123 - a chapter titled Night Fighter. Brigadier General Frank Hawse Schwable retired from active duty June 30, 1959, following 30 years' service in the Marine Corps.

He was promoted to brigadier general on retirement by reason of having been specially commended for heroism in combat during World War II. A 1929 graduate of the U. Naval Academy and a Marine aviator since 1932, Schwable flew more than 72 combat missions in World War II, and was the creator and commander of the first night fighter squadron to see action in the Pacific. He was awarded four Distinguished Flying Crosses and ten Air Medals for his participation in the consolidation of the Northern Solomons, in the New Georgia and Treasury-Bougainiville campaigns, and in the occupation of the Bismarck Archipelago. He earned his first Legion of Merit while commanding Marine Night Fighter Squadron 531, and his second for services in various capacities with the First Marine Aircraft Wing and on the Staff of the Commander, Aircraft, Northern Solomons.

Born July 18, 1908, at Norfolk, Virginia, Schwable is the son of the late Marine Colonel Frank J. Schwable, a Boxer Rebellion and Philippine Insurrection veteran.

Attending Pen Charter School at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, until 1923, General Schwable completed his preparatory course at the Severn School in Severna Park, Maryland, in 1925. He then entered the U. Naval Academy, and was commissioned a Marine second lieutenant upon graduation, June 6, 1929. After a brief service with the rifle range detachment at Quantico, Virginia, he entered Officers Basic School at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in August 1929. On completing Basic School in July 1930, he entered pre-flight training at the Naval Air Station, Norfolk, Virginia, and in September began flight training at Pensacola, Florida.

In January 1932, Schwable embarked for South America, to begin serving with the Marine Utility Squadron 6-M in Nicaragua. There he won the Nicaraguan Cross of Valor (an extremely rare medal) for meritorious service in attacks on armed bandits. He was cited for his aid to ground troops searching for survivors of crash landings in the jungle. Returning to the United States in January 1933, Schwable served as a pilot and gunnery and aviation officer at Quantico until June 1936.

He was then ordered to the Naval Air Station, San Diego, California, where he served as a personnel officer, communications officer, and pilot until February 1939. Schwable transferred to Washington, D. The following month, serving in the Plans Section, Aeronautics Division, Navy Department, until November 1941. In December 1941, Schwable was designated a special Naval observer with the British RAF, serving in North Africa, and then in England where the British briefed him on their secret weapon - radar, and its application in a new kind of warfare called night fighting.

Night fighters were a special breed of daring airmen; they flew modified aircraft, stalking their prey in total darkness, coached into an attack position behind an unsuspecting enemy aircraft with the aid of special radar devices. Only moments before the attack would the enemy reveal itself, as a dark silhouette against a starry sky. The squadron, VMF(N)-531, proved itself in 1943 in the Solomon Island campaign where Schwable served as squadron commander. By February 1944 he had logged 72 combat missions for a total of 421 hours in the combat zone with four kills; one more and he would have become the first night fighter ace of the Pacific War.

The morning after his fourth air victory, Schwable was called over to breakfast with Major General Ralph Mitchell, Commander of Allied Air Units in the Solomons. Schwable's hands shook as he raised his coffee cup, from the strain of unrelenting combat. Not wanting to risk loosing an officer of such caliber, Mitchell ordered Schwable to take a month's rest and report back for lighter duty as Operations Officer, Fighter-Strike Command, Air North Solomons, to direct daily airstrikes against the enemy stronghold at Rabaul.

Stunned and in disbelief, Schwable pleaded with Mitchell to let him stay on a little longer "to get a few more planes, " but Mitchell refused. The following day, Colonel Clayton Jerome put him aboard the next flight to Australia, "It takes a strong man to cry, " recalled Jerome, There were deep tears in his eyes. He wanted to stay right there and fight. New assignments followed as the Corps groomed Schwable for promotion to general. From February 1944 until June 1946, he was stationed in Washington, D.

Where he was Assistant Air Plans officer in the Strategic Plans Section, Operations Division, in the offices of the Commander in Chief, U. Feet, and the Chief of Naval Operations. In September 1946, after he entered the National War College (completing the course in 1947) he served for a year as commander of Marine Aircraft Group 12 at the Marine Corps Air Station, El Toro, California. Named head of the Operations and Training Branch in August 1951, he served in that capacity until October when he became Deputy Assistant Director and Executive officer of the Division of Aviation. In April 1952, Schwable embarked for Korea where he became Chief of Staff of the First Marine Aircraft Wing.

On July 8, Schwable boarded a twin-engine aircraft with his co-pilot Major Bley, to see firsthand the area of operations over which he would soon command. During the flight a strong wind and compass variations caused Schwable and Bley to lose their bearings. When the aircraft had strayed three miles behind enemy lines, a stream of tracers passed just off the right wing. Then a series of loud crashes were heard on the right side of the cockpit as bullets pierced the airframe, striking Bley in his thighs.Schwable turned south, gunned the engines and started to climb when both engines stopped without a sputter - a bullet had cut the main fuel line. Schwable leveled of, and pushed Bley out of the aircraft, following close behind. Rather than make an easy escape south, Schwable went north to aid Bley who had landed a few hundred yards away.

While in a tree, cutting down Bley's parachute for bandages, a group of Korean soldiers approached and took the two men as prisoners, making Schwable the second-highest ranking POW of the war. The Chinese wanted more than Schwable's physical capture - his mind too would be forced to surrender. The Chinese were convinced that the United States Government was conducting germ warfare on the Korean Peninsula.

If an officer of Schwable's rank could be forced to make a germ warfare confession, then the Communists would win a major propaganda victory. To force him to "confess" to their lie, the Chinese used menticde, a new form of mental torture developed by the Soviet Union. It combined extreme isolation with prolonged, repetitive interrogation to undermine the conscious mind, allowing the interrogator to extract from his victim whatever words desired.

Hostilities on the Korean Peninsula ended on July 27, 1953. After taking a shower and one day of rest, Schwable was put aboard the USS General R. Howze, bound for San Francisco.

During the voyage he prepared a type-written account of his ordeal - pages cluttered with scratched-out passages and penciled-in corrections. His eyes, like haunted caverns dug into hollow cheeks, spoke more elegantly than words as he struggled to explain his strange ordeal that he suffered at the hands of his captors.Schwable spent most of his time as a POW imprisoned in a 4 x 7 foot unheated lean-to, isolated without human contact - except for his interrogator. Like a beast in a cage, wallowing in his own filth, Schwable was forced to sit cross-legged, at attention, as the hard-boiled interrogations droned on, day after day, for months. The same material was repeated over and over until the past became a confusing mix of fact and fiction.

By November the full effects of menticide began to appear; he had become mentally dull, unresponsive, and stupid in his reactions. After passing out during a latrine call, Schwable became alarmed by his deteriorating health. Further resistance, he reasoned, would be both fatal and futile. Although Schwable did not use the words "Yes, I confess" that night, he did in so many words admit guilt.

This triggered another interrogation, accompanied by almost continuous writing as he struggled to invent a story about germ warfare that would pacify his captors. As he fabricated his story the weather grew colder and the ink in his pen froze after every few words written. In his mind's eye he imagined himself in conference with General Jerome, mumbling aloud, discussing with Jerome the problems involved in germ warfare. He used his imagination to such an extent that he began to live and dream the various elements of his fabrication as if they were real. By mid-December the remote camp closed and Schwable was moved with eighteen other American GIs by truck to Main camp 5 in Pyoktong. During the ride Schwable he began twitching, and flung his arms about like a punch drunk prize fighter. At one point during the ride he jumped up and cried out; I'm surrounded by oil! What's all this oil doing here? He was silenced by the guard. At the Main Camp, Schwable was forced to continue his "confession" until the revisions had satisfied his interrogating officer.When the papers cleared high command, he was handed a revised 6,000 word type-written statement and was told to copy it. "There is just one more final step, " the chief interrogator said as he handed Schwable the revised statement.

You must be filmed reading your confession. Before appearing on camera, Schwable was allowed to bathe for the first time since his capture, and was given a new uniform.

In a dress rehearsal the night before filming, Schwable was introduced to the British Communist Daily Worker correspondent Allen Winington. Schwable hated Winington bitterly for what he represented, but nevertheless was happy to talk with an English-speaking man for the first time in eight months. All was not as it seemed.

Winington cleverly waited for the motion picture crew to man their cameras, and then made a funny remark. When Schwable laughed, the cameras clicked, portraying the Colonel as a happy-go-lucky willing to slander his own country. The Corps reeled at the news of his confession.

A rumor circulated that the Marine Corps Commandant told Schwable, after his return to the United States, that his actions had set the Corps back fifty years. On January 24, 1953, the Corps Commandant appointed a board of inquiry to determine whether Schwable should be court martialed for having been unfaithful unto death to the Corps motto, Semper Fidelis , or if his false confession was justified by the contention that every man has his breaking point and any man can be conditioned by torture. When Schwable took the stand before the Court of Inquiry, he appeared thin an nervous after fourteen months of solitary confinement.As he spoke, the flow of words became so rapid and continuous that one could scarcely keep pace. With his words he sketched for the court a portrait of a highly sensitive man, a trait rare among carer military men, yet capable of driving himself to acts of heroism in the Solomon Islands. Schwable explained that he understood a military man is obligated to die defending his country if need be, and that his record during World War II should stand on its own merits as proof of his willingness to expose himself. But he also expected to be protected by international law and by the regulations regarding officer POWs, and how it slowly dawned on him that instead, he was being subjected to a new kind of interrogation; subjected to hunger and exposure to extreme cold; not allowed to wash or shave and was surrounded by filth and vermin.

His decision to sign a false confession had been no decision at all, but rather a crumbling of his mind and will so that no other alternative was possible, and how unprepared he was for such treatment. When asked whether he ever believed the United States had engaged in bacteriological warfare, Colonel Schwable sat straight back in his chair, paused a moment and said, I knew that the 1st Marine Wing didn't, but the rest of my'confession' was real to me - the imagined conferences, the planes, and how they would go about their missions. That was the hardest thin to explain. I knew it was false.

" Then he stopped a minute and in a choking voice with his hands flailing around, trying to explain what had happened even thou the words wouldn't, "I can't explain how you can sit down and write something you know is false - not to believe it, " and then he paused for a moment, "to live it. Schwable's case was a media sensation. For many, his story was a poignant tragedy; evidence that the military failed to prepare soldiers for this new mode of warfare. If an officer of Schwable's caliber could break under the psychological lash, so could others unless they were schooled to fight back.

For others, his false confession made him a disgrace - he was a fallen Marine. In the end, the Board of Inquiry determined that Colonel Schwable resisted torture to the limit of his ability and recommended that he not be disciplined.

However his usefulness as an officer had been seriously impaired, and never again would he be allowed to command troops in the field. One positive outcome of the trial was the creation of the Code of Conduct for Members of the United States Armed Forces, a six point ethical guide for captured American prisoners that in effect to this day. Schwable passed his remaining years in the Corps investigating accident reports. When he retired on June 30, 1959, his commanding officer Ziggy Dawson refused to attend the ceremony.

A junior officer was chosen in his place to pin a pair of Brigadier generals one-star insignia onto his collar - a promotion awarded for heroism in combat during the Second World War. Schwable retired to his farm in Virginia the following day, and never piloted an airplane again. The item "WWII Korean War Group of Historical Signifcance Frank Schwable USMC" is in sale since Monday, January 27, 2020.

This item is in the category "Collectibles\Militaria\WW II (1939-45)\Original Period Items\United States\Other US WWII Original Items". The seller is "pollard5583" and is located in Blue Earth, Minnesota.

This item can't be shipped, the buyer must pick up the item.